Seijun Suzuki

- senseabove

- Joined: Wed Dec 02, 2015 3:07 am

Re: Seijun Suzuki

Thanks for the update, feihong, and the bonus Suzuki info. Very glad to hear it looks good.

No idea about actual UHD playback software for Mac, but per a guide you should be able to dig up with all of the keywords in the rest of this sentence, I put an ASUS BW-16D1HT in an OWC Mercury Pro 5.25" external enclosure, flashed it, and have used it to rip UHDs and BDs on a Mac.

EDIT: It's up on backchannels so here're the closest matching shots of the remux from those sources and available caps (from DVDBeaver's Arrow set review) I could find, and wow:

Zigeunerweisen

Kagero-Za 1, 2

No idea about actual UHD playback software for Mac, but per a guide you should be able to dig up with all of the keywords in the rest of this sentence, I put an ASUS BW-16D1HT in an OWC Mercury Pro 5.25" external enclosure, flashed it, and have used it to rip UHDs and BDs on a Mac.

EDIT: It's up on backchannels so here're the closest matching shots of the remux from those sources and available caps (from DVDBeaver's Arrow set review) I could find, and wow:

Zigeunerweisen

Kagero-Za 1, 2

Last edited by senseabove on Mon Apr 22, 2024 4:58 pm, edited 1 time in total.

- fdm

- Joined: Fri Apr 21, 2006 1:25 pm

Re: Seijun Suzuki

Regarding the player link above in nicolas's post, skimmed through the listing and its user reviews:

"For the MacOS there is no runable official playback software for purchased UHD movies! " per that player's amazon listing.

However, one user review claims that Leawo Blu-ray Player "plays blu-ray and 4k uhd without problems" (macOS Sonoma). Whether that means directly playing movies, or…

Another user review indicates using makemkv and vlc as a possible solution…

And senseabove's post seems to confirm (?)…

Those and maybe a virtualized Windows solution (one of my own thoughts) for direct playback ?? …

Maybe I'll get some time to pursue this further, though later in the year.

"For the MacOS there is no runable official playback software for purchased UHD movies! " per that player's amazon listing.

However, one user review claims that Leawo Blu-ray Player "plays blu-ray and 4k uhd without problems" (macOS Sonoma). Whether that means directly playing movies, or…

Another user review indicates using makemkv and vlc as a possible solution…

And senseabove's post seems to confirm (?)…

Those and maybe a virtualized Windows solution (one of my own thoughts) for direct playback ?? …

Maybe I'll get some time to pursue this further, though later in the year.

-

nicolas

- Joined: Sat Apr 29, 2023 11:34 am

Re: Seijun Suzuki

The player is compatible with both Mac and Windows. I have a Mac setup and a Parallels virtual machine and you can seamlessly switch inputs to “move” the player between macOS and Windows for everything you do. On Mac, it works for ripping purposes (MakeMKV) and in my case if you want to burn discs, I’ll use Windows and that works just as well. It’s not the quietest device but I don’t mind.fdm wrote: ↑Sat Apr 20, 2024 3:05 pmRegarding the player link above in nicolas's post, skimmed through the listing and its user reviews:

"For the MacOS there is no runable official playback software for purchased UHD movies! " per that player's amazon listing.

However, one user review claims that Leawo Blu-ray Player "plays blu-ray and 4k uhd without problems" (macOS Sonoma). Whether that means directly playing movies, or…

Another user review indicates using makemkv and vlc as a possible solution…

And senseabove's post seems to confirm (?)…

Those and maybe a virtualized Windows solution (one of my own thoughts) for direct playback ?? …

Maybe I'll get some time to pursue this further, though later in the year.

I had to replace the first model I received as I kept getting an error when attempting to import discs but the manufacturer’s customer support is above and beyond friendly in getting this sorted out. I immediately got sent a brand new set and got a free mailing label for returning my damaged one.

I don’t have a disc playback software / app for both Windows and Mac as I only use the player for ripping discs. Around 10 years ago, I had good experiences with CyberLink on Windows for BD playback.

- feihong

- Joined: Thu Nov 04, 2004 12:20 pm

Re: Seijun Suzuki

Thanks very much for all the suggestions! I have the software, but I couldn't find a player that worked for Mac until now, that I didn't have to flash (just don't want to deal with that kind of stuff any more). I'm gonna try that German drive.

- feihong

- Joined: Thu Nov 04, 2004 12:20 pm

Re: Seijun Suzuki

FIGHTING ELEGY

Behind the curve on the Nikkatsu sets, here's what I've got on Fighting Elegy. The info I got off the disc said that the Trailer for the film was Progressive, and that the feature was interlaced. So I'll compare some shots. Some of these won't be 100% matches, because, as it turns out, the trailer seems to use some alternate takes! Pretty interesting to see the differences.

[TEXT ONLY]

[TEXT & IMAGES]

Behind the curve on the Nikkatsu sets, here's what I've got on Fighting Elegy. The info I got off the disc said that the Trailer for the film was Progressive, and that the feature was interlaced. So I'll compare some shots. Some of these won't be 100% matches, because, as it turns out, the trailer seems to use some alternate takes! Pretty interesting to see the differences.

[TEXT ONLY]

SpoilerShow

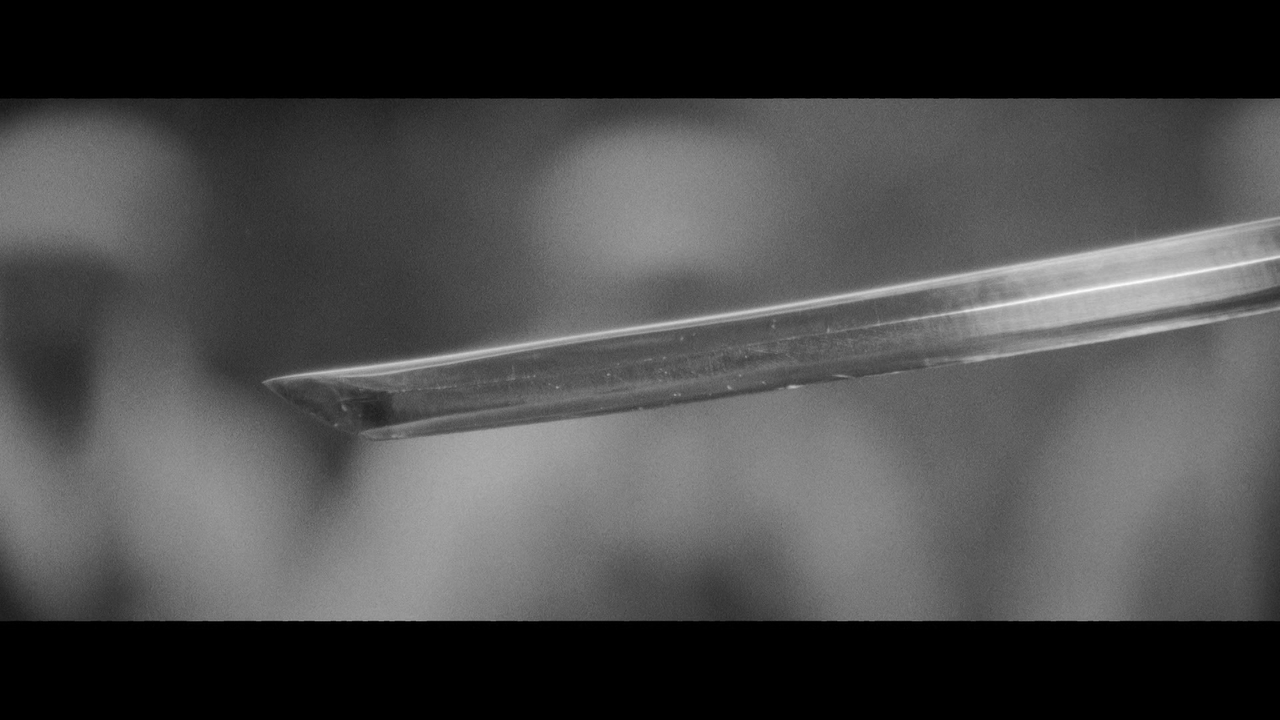

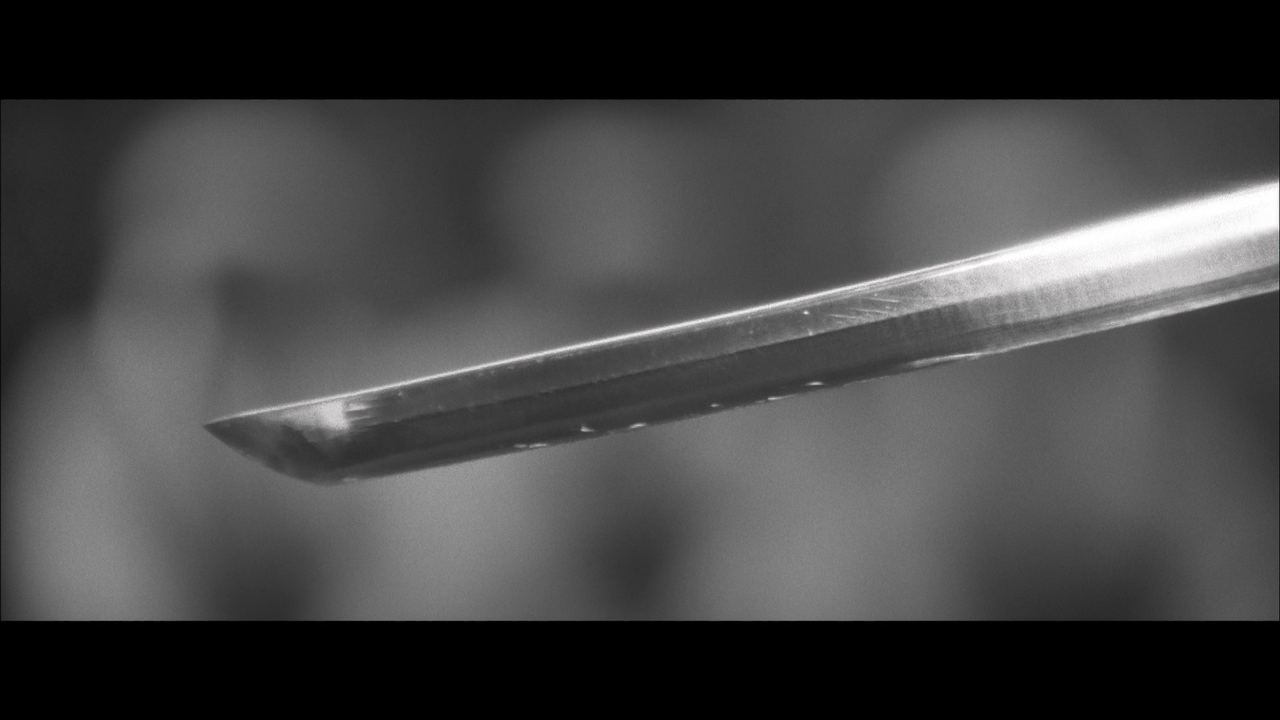

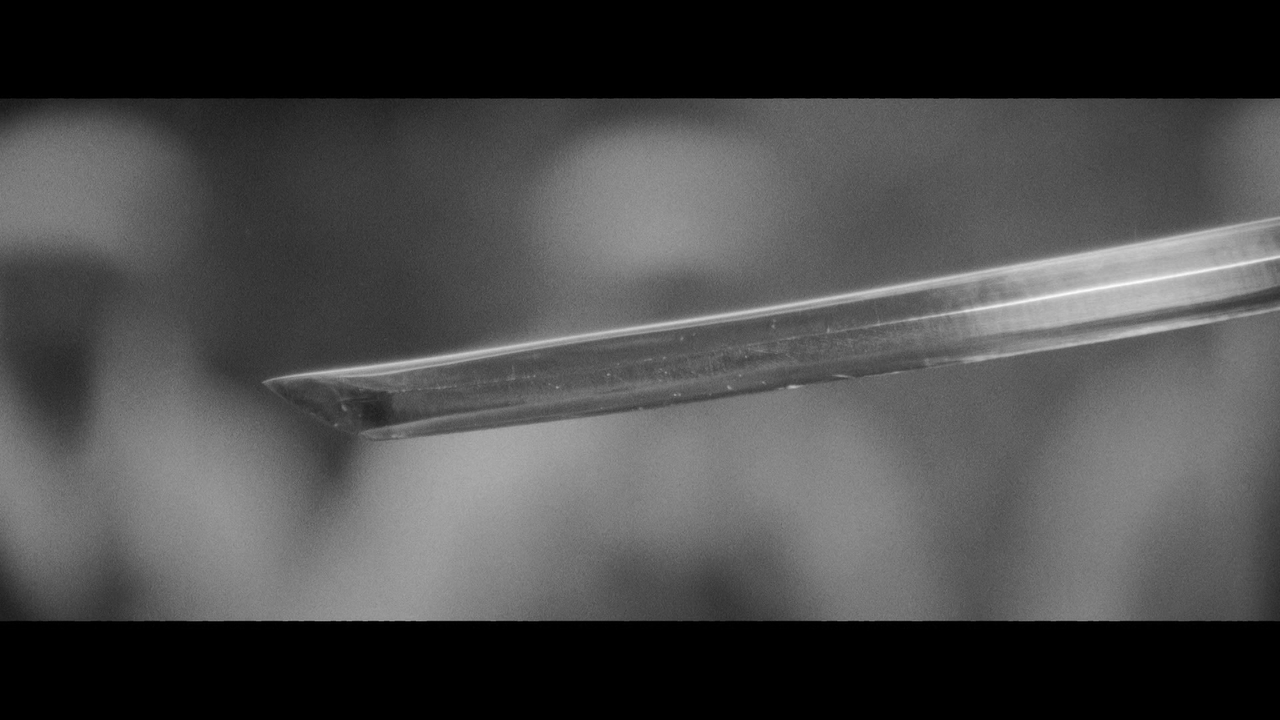

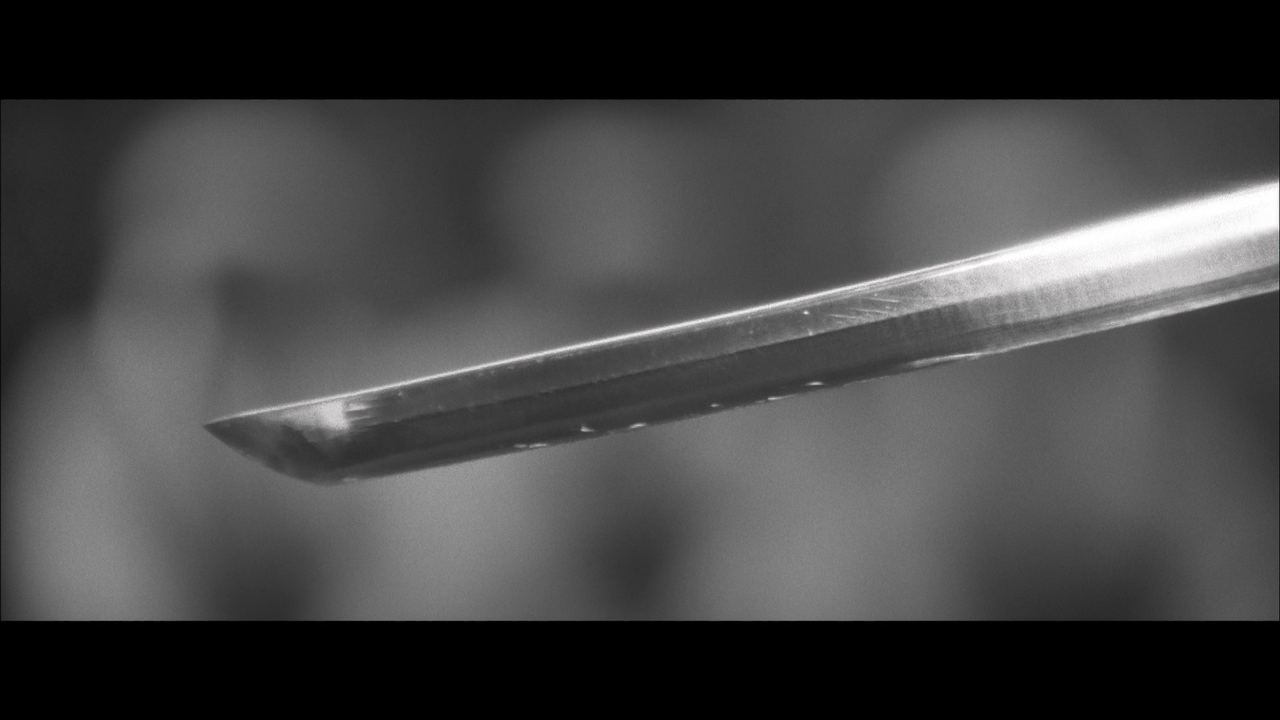

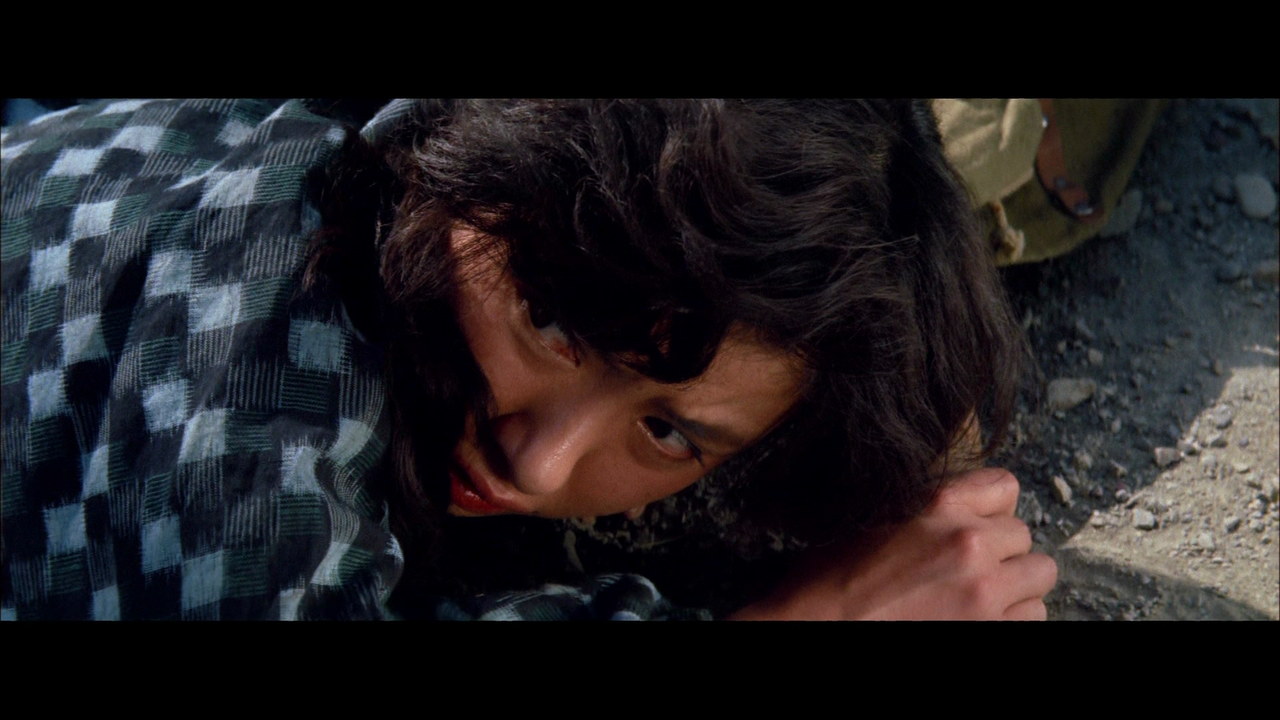

Where you see different matches, it's because the footage in the trailer seems to be either from a section of the shot which was edited out of the final film (i.e., the finger-biting closeup, the prostitute standing under the canted roof), or, in the case of the shots where Kiroku sits on the tower, the one of Kiroku pulling Michiko along, or the more subtly differing shot of the youth gang meeting in the forest, these are alternate takes with adjustments of camera positioning and with different amounts of debris in the air. But I think you can see the differences we were talking about earlier in the thread. It looks to me like the trailer has much better grain, much better contrast, and is without the pastiness in skin tons and other gradient textures (the shine on the closeup of the sword tip, for instance). My impression is that in the "Seijun on Women" boxset, the transfers looked better––though they are still listed as interlaced. I'll post shots from Kanto Wanderer from that box next., then maybe Love Letter, with its 4k scan and progressive encoding (not sure I'm using the terms right––I'm doing my best to learn how you experts judge these things).

SpoilerShow

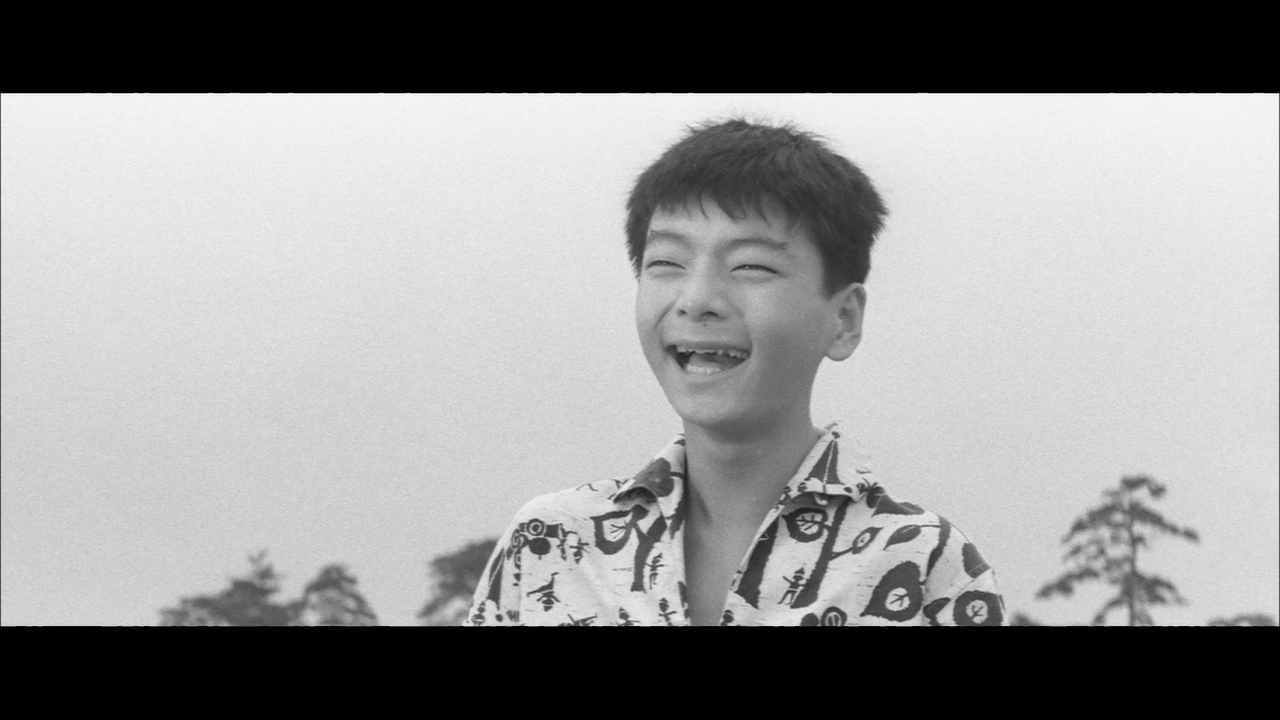

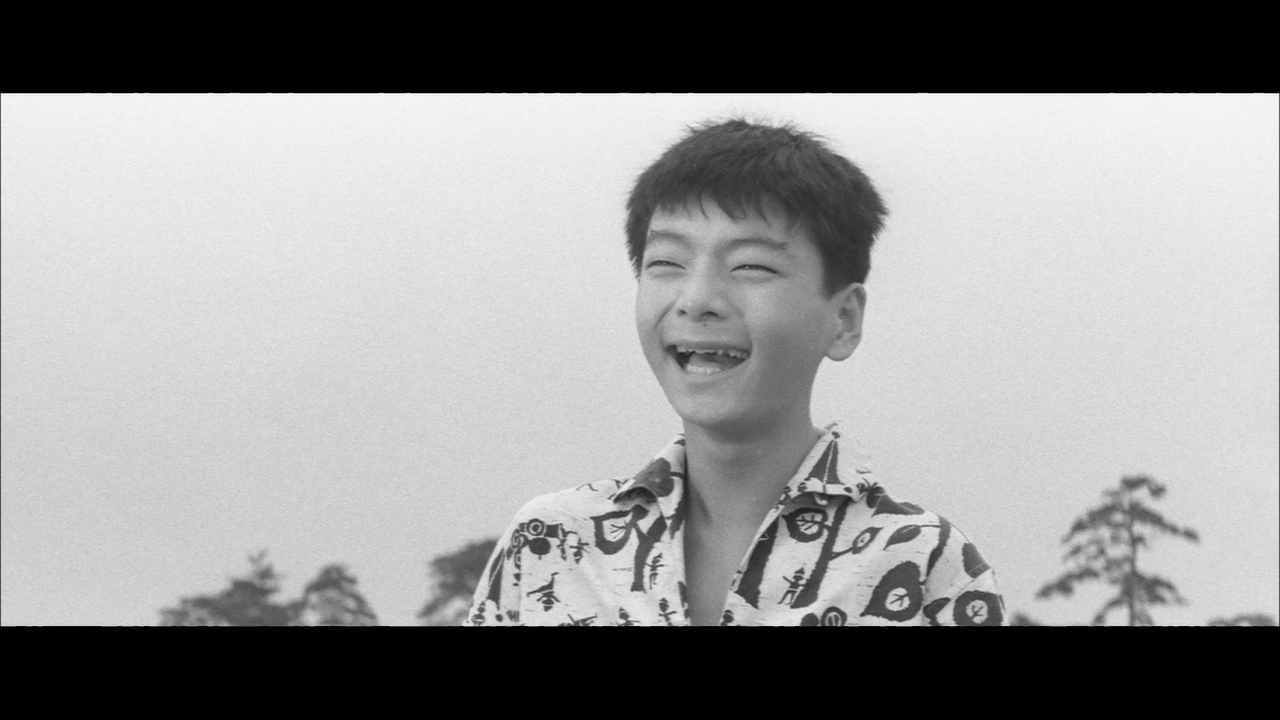

Trailer

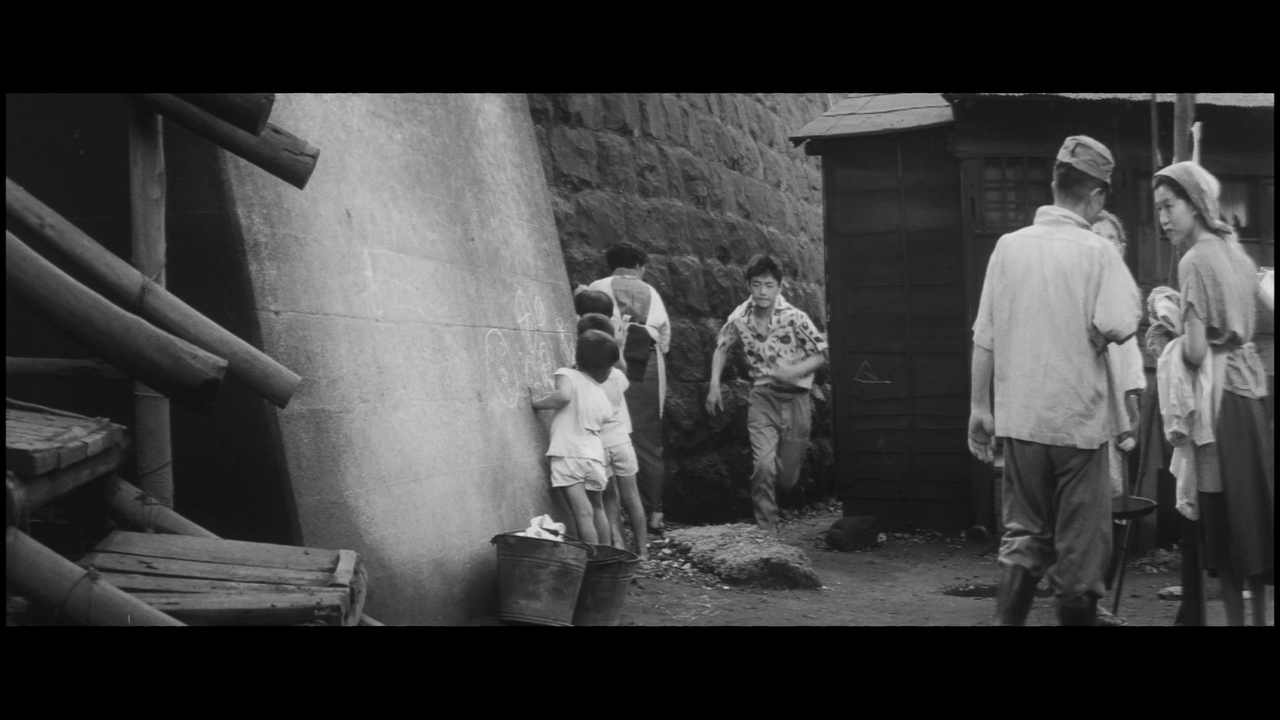

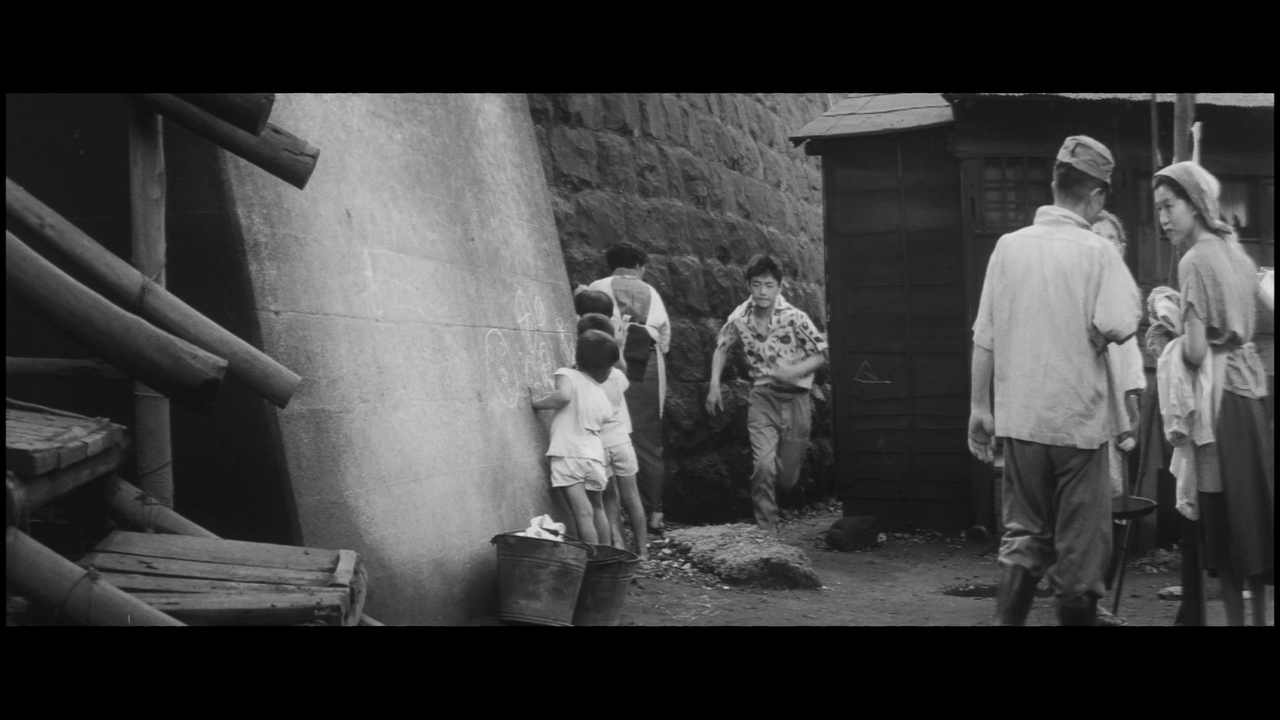

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Where you see different matches, it's because the footage in the trailer seems to be either from a section of the shot which was edited out of the final film (i.e., the finger-biting closeup, the prostitute standing under the canted roof), or, in the case of the shots where Kiroku sits on the tower, the one of Kiroku pulling Michiko along, or the more subtly differing shot of the youth gang meeting in the forest, these are alternate takes with adjustments of camera positioning and with different amounts of debris in the air. But I think you can see the differences we were talking about earlier in the thread. It looks to me like the trailer has much better grain, much better contrast, and is without the pastiness in skin tons and other gradient textures (the shine on the closeup of the sword tip, for instance). My impression is that in the "Seijun on Women" boxset, the transfers looked better––though they are still listed as interlaced. I'll post shots from Kanto Wanderer from that box next., then maybe Love Letter, with its 4k scan and progressive encoding (not sure I'm using the terms right––I'm doing my best to learn how you experts judge these things).

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Where you see different matches, it's because the footage in the trailer seems to be either from a section of the shot which was edited out of the final film (i.e., the finger-biting closeup, the prostitute standing under the canted roof), or, in the case of the shots where Kiroku sits on the tower, the one of Kiroku pulling Michiko along, or the more subtly differing shot of the youth gang meeting in the forest, these are alternate takes with adjustments of camera positioning and with different amounts of debris in the air. But I think you can see the differences we were talking about earlier in the thread. It looks to me like the trailer has much better grain, much better contrast, and is without the pastiness in skin tons and other gradient textures (the shine on the closeup of the sword tip, for instance). My impression is that in the "Seijun on Women" boxset, the transfers looked better––though they are still listed as interlaced. I'll post shots from Kanto Wanderer from that box next., then maybe Love Letter, with its 4k scan and progressive encoding (not sure I'm using the terms right––I'm doing my best to learn how you experts judge these things).

Last edited by feihong on Sat Dec 14, 2024 8:53 am, edited 1 time in total.

- feihong

- Joined: Thu Nov 04, 2004 12:20 pm

Re: Seijun Suzuki

Incredibly, Nikkatsu is putting out a third blu ray boxset now, due out September 4th: "Seijun on Wanderers." The emphasis seems to be much more on color films than the previous releases, and the box art reflects that, with an emphasis on the intense color of Tokyo Drifter.

I had a hard time finding all the films listed online, and I can't tell if any of them have 4k scans this time around, but the films being released mostly correspond to what is already available in 1080p and has already been released in other regions, and what has been traveling around the internet in 1080p transfers recently:

Tokyo Drifter

Tattooed Life

Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards!

The Flower and the Angry Waves

Hi-Teen Yakuza

Fighting Delinquents aka Go To Hell, Youth Gangs!

An Inn of Floating Weeds.

Hi-Teen Yakuza and An Inn of Floating Weeds are the only black-and-white films in the group. Disappointing, of course, that I'll be double-dipping on Tattooed Life, all things considered. I've seen a gorgeous 1080p version of The Flower and the Angry Waves already (also saw it in 35mm at the Egyptian one time), and I've seen a very nice hi-def version of An Inn of Floating Weeds. Flower and the Angry Waves and Fighting Delinquents are the ones I'm most looking forward to––cinematographer Shigeyoshi Mine is generally held up as the great color cinematographer of Suzuki's Nikkatsu career, but these two films offer samples of Kazue Nagatsuka's color cinematography, which I really love. Mine does great color schemas, especially in Tokyo Drifter, Kanto Wanderer and Gate of Flesh, but I remember particular colors and scenes from Nagatsuka's color work so vividly––scenes from Zigeunerweisen and Mirage Theater that just ripple with incredible color choices. Fighting Delinquents previously had a very poor DVD transfer, which didn't wow me, but seeing the film on 35mm was a revelation––the colors just vibrate with intensity––it literally makes the movie better, and changed my impression of the film in general. I don't know how I'm going to swing the price tag on this box, and it's likely the interlaced transfers will continue to be a problem (so far they've done two 4k transfers per box––if they keep it up, I would bet Tokyo Drifter and either Tattooed Life or Fighting Delinquents would be the second one), but it somehow must be done.

I can't imagine this is anything but the last of these sets from Nikkatsu––even though there is unreleased Nikkatsu material that they have in HD, like Singing Rope: Innocent Love at Sea, A Hell of a Guy aka Living By Karate, and, apparently, Blue Breasts. But I don't think they have another film from the Nikkatsu era that is a headliner for a fourth box, unless you want to get down to something like Underworld Beauty or The Wind-0f-Youth Group Goes Over the Mountain Pass. I'd say that, except for the other Koji Wada movies, they've mostly covered all the color pictures. In that sense, they've covered the color pictures that are considered the major cannon.

I had a hard time finding all the films listed online, and I can't tell if any of them have 4k scans this time around, but the films being released mostly correspond to what is already available in 1080p and has already been released in other regions, and what has been traveling around the internet in 1080p transfers recently:

Tokyo Drifter

Tattooed Life

Detective Bureau 2-3: Go to Hell, Bastards!

The Flower and the Angry Waves

Hi-Teen Yakuza

Fighting Delinquents aka Go To Hell, Youth Gangs!

An Inn of Floating Weeds.

Hi-Teen Yakuza and An Inn of Floating Weeds are the only black-and-white films in the group. Disappointing, of course, that I'll be double-dipping on Tattooed Life, all things considered. I've seen a gorgeous 1080p version of The Flower and the Angry Waves already (also saw it in 35mm at the Egyptian one time), and I've seen a very nice hi-def version of An Inn of Floating Weeds. Flower and the Angry Waves and Fighting Delinquents are the ones I'm most looking forward to––cinematographer Shigeyoshi Mine is generally held up as the great color cinematographer of Suzuki's Nikkatsu career, but these two films offer samples of Kazue Nagatsuka's color cinematography, which I really love. Mine does great color schemas, especially in Tokyo Drifter, Kanto Wanderer and Gate of Flesh, but I remember particular colors and scenes from Nagatsuka's color work so vividly––scenes from Zigeunerweisen and Mirage Theater that just ripple with incredible color choices. Fighting Delinquents previously had a very poor DVD transfer, which didn't wow me, but seeing the film on 35mm was a revelation––the colors just vibrate with intensity––it literally makes the movie better, and changed my impression of the film in general. I don't know how I'm going to swing the price tag on this box, and it's likely the interlaced transfers will continue to be a problem (so far they've done two 4k transfers per box––if they keep it up, I would bet Tokyo Drifter and either Tattooed Life or Fighting Delinquents would be the second one), but it somehow must be done.

I can't imagine this is anything but the last of these sets from Nikkatsu––even though there is unreleased Nikkatsu material that they have in HD, like Singing Rope: Innocent Love at Sea, A Hell of a Guy aka Living By Karate, and, apparently, Blue Breasts. But I don't think they have another film from the Nikkatsu era that is a headliner for a fourth box, unless you want to get down to something like Underworld Beauty or The Wind-0f-Youth Group Goes Over the Mountain Pass. I'd say that, except for the other Koji Wada movies, they've mostly covered all the color pictures. In that sense, they've covered the color pictures that are considered the major cannon.

- feihong

- Joined: Thu Nov 04, 2004 12:20 pm

Re: Seijun Suzuki

I found the more in-depth writeup on the upcoming Suzuki box, and, in a bit surprise, it looks like now there are 3 films getting 4k scans. They are:

Tokyo Drifter

Fighting Delinquents aka Go To Hell, Youth Gangs!

An Inn of Floating Weeds

The Tokyo Drifter 4k scan is also being advertised as a "digitally restored version," as was Branded to Kill on the first boxset. That disc in the first set looked great––probably the best of any of the discs in these sets so far––so hopefully this bodes well for Tokyo Drifter. I love the 4k scans that haven't been restored, with all the pops and scratches, like Carmen from Kawachi––and I wish all of these had this treatment––but Tokyo Drifter on Criterion had room for some tightening and improvement, so I feel like this could be a real revelation. Like the other Suzuki movies shot in color by Shigeyoshi Mine (Kanto Wanderer, Gate of Flesh, Our Blood Will Not Forgive), there is a range of subtle lighting effects that could look a whole lot better with improved picture quality.

I didn't expect that, but this should be pretty cool. Even though I can't really afford it, I'm hoping this will result in a 4th Suzuki boxset, maybe with a 4k of Satan Town, Underworld Beauty, and/or Blue Breasts. William Carroll's analysis of Blue Breasts makes it sound like a really intriguing movie.

Tokyo Drifter

Fighting Delinquents aka Go To Hell, Youth Gangs!

An Inn of Floating Weeds

The Tokyo Drifter 4k scan is also being advertised as a "digitally restored version," as was Branded to Kill on the first boxset. That disc in the first set looked great––probably the best of any of the discs in these sets so far––so hopefully this bodes well for Tokyo Drifter. I love the 4k scans that haven't been restored, with all the pops and scratches, like Carmen from Kawachi––and I wish all of these had this treatment––but Tokyo Drifter on Criterion had room for some tightening and improvement, so I feel like this could be a real revelation. Like the other Suzuki movies shot in color by Shigeyoshi Mine (Kanto Wanderer, Gate of Flesh, Our Blood Will Not Forgive), there is a range of subtle lighting effects that could look a whole lot better with improved picture quality.

I didn't expect that, but this should be pretty cool. Even though I can't really afford it, I'm hoping this will result in a 4th Suzuki boxset, maybe with a 4k of Satan Town, Underworld Beauty, and/or Blue Breasts. William Carroll's analysis of Blue Breasts makes it sound like a really intriguing movie.

Last edited by feihong on Thu Aug 29, 2024 5:16 am, edited 1 time in total.

- ryannichols7

- Joined: Mon Jul 16, 2012 2:26 pm

Re: Seijun Suzuki

the new Tokyo Drifter restoration is playing (or has played) at least one western festival too. I'm hoping Criterion see it fit to bring to UHD stateside - their Branded to Kill disc remains one of the best/coolest surprises they've put out on the format so far. while I hope to see more Suzuki restorations come to disc in the west (especially for films without Blurays so far), Tokyo Drifter remains my favorite, so I do hope to see it happen...Suzuki's use of color in 4K is something I really need to see!

- feihong

- Joined: Thu Nov 04, 2004 12:20 pm

Re: Seijun Suzuki

Life came crashing down around my ears in the last couple of months, and I stopped posting screencaps from the various Suzuki blu ray releases. I imagine this will go slowly, but I hope to keep it up. It's a way to celebrate my favorite filmmaker, and his centenary, I guess. Disappointing that neither Criterion nor Arrow did anything in that regard.

KANTO WANDERER

Time to share some stuff from the second blu ray collection, Seijun on Women; here's probably my favorite of the Nikkatsu movies, Kanto Wanderer. This movie had a DVD release from way back, via HomeVision, which was good enough for the time, but not really adequate to convey the subtle virtues of the movie (a Japanese DVD proved to be pretty much the same in that regard). Seeing the film in 35mm at the Hammer Museum revealed a lot of the sophistication of the image––especially in lighting. But there was depth to the image as well, and boldness to the colors. Peter A. Yacavone talks quite a bit about Kanto Wanderer in his incredible new book on Suzuki––he identifies it as the film on which the sort of creative brain trust of Suzuki's later films really starts to cohere.

[TEXT ONLY]

[TEXT & IMAGES]

KANTO WANDERER

Time to share some stuff from the second blu ray collection, Seijun on Women; here's probably my favorite of the Nikkatsu movies, Kanto Wanderer. This movie had a DVD release from way back, via HomeVision, which was good enough for the time, but not really adequate to convey the subtle virtues of the movie (a Japanese DVD proved to be pretty much the same in that regard). Seeing the film in 35mm at the Hammer Museum revealed a lot of the sophistication of the image––especially in lighting. But there was depth to the image as well, and boldness to the colors. Peter A. Yacavone talks quite a bit about Kanto Wanderer in his incredible new book on Suzuki––he identifies it as the film on which the sort of creative brain trust of Suzuki's later films really starts to cohere.

[TEXT ONLY]

SpoilerShow

The disc scans like the other non-4k scans in these collections, as 1080i, with a 1080p trailer attached. In those cases on the previous set, Seijun on Men, the result was pretty clear across the board––in each case, the trailer had a sharper image, with more depth, and things like movement looked more dynamic overall. Kanto Wanderer, however is quite different. For starters, the trailer seems more damaged than those on the other films. But secondly, the feature on this disc looks great, in spite of technical limitations. Perhaps because previous versions were quite poor, I'm weighting it more favorably. But this is one of the discs in the set where the feature looks most special. Color and contrast are improved from the trailer, but there is also a cleaner grain structure, which looks finer to me. While it's playing, the feature has a lot of depth and visual sophistication. It isn't as sharp as the 4k transfers, to be sure, but it looks beautiful all the same.

Here are my comparisons to the trailer. Another note needs be added here for the comparisons––as with Fighting Elegy, it was impossible to match most of the captures exactly, because the trailer uses a lot of alternate takes of shots. In terms of Kanto Wanderer, virtually every shot was an alternate, with subtle adjustments to camera position and with the actors delivering different timing.

This persists throughout the comparison. The saturation of colors on the feature is much closer to what was presented when I saw the film in 35mm. In fact, all of Suzuki's color films from Nikkatsu which I've seen in 35mm have at least this saturated a color scheme (I haven't seen a lot of the more muted–seeming color films in 35mm––neither of the boxing movies, for example, or A Hell of a Guy, which seems to have a strong blue/yellow bias––but I did see Our Blood Will Not Forgive, which is more muted and blue than the other films of this era, and the more blue-and-grey color palette of that film was still quite saturated. There were some differences between the films with Shigeyoshi Mine as cinematographer––which tended to foreground these big panels of saturated color––and the ones where Kazue Nagatsuka shot them––he tended to highlight smaller, more subtle color expressions––and then there was some difference with films shot by other cinematographers, like Tattooed Life and Story of Sorrow and Sadness). To my eyes, the feature has much more depth-of-field here––maybe partly due to the broader range of contrast present in the feature transfer.

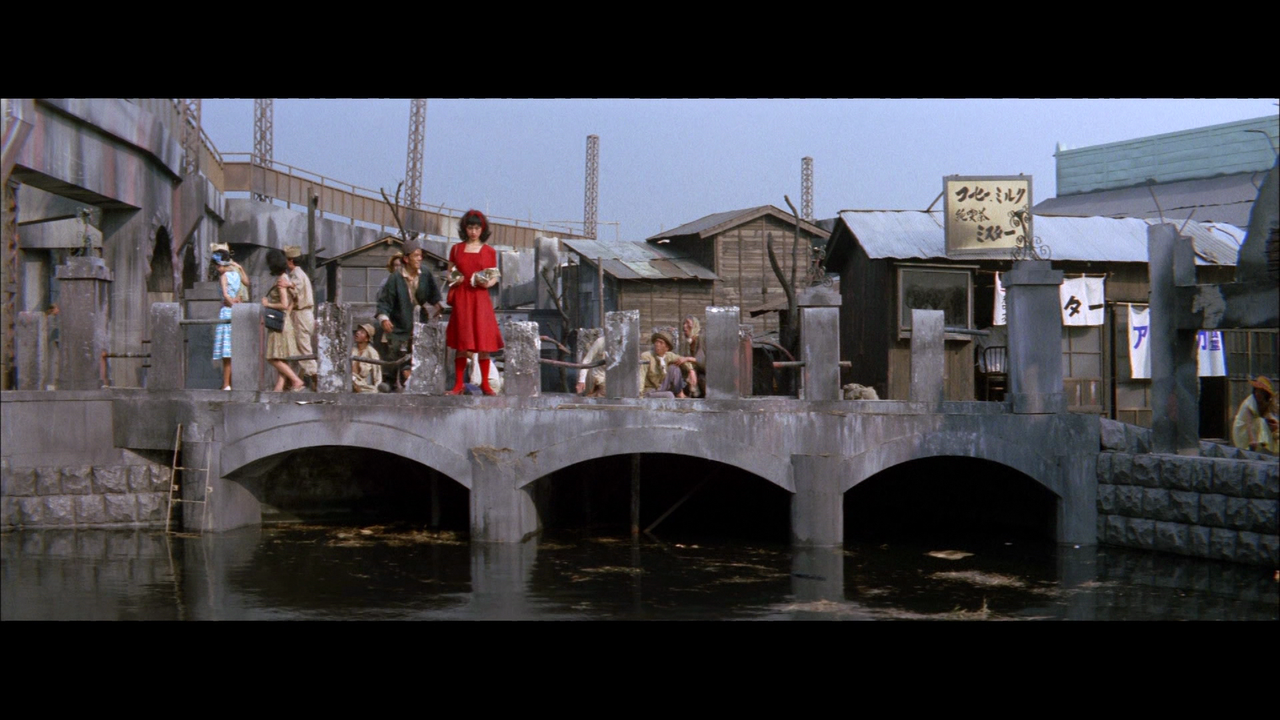

Who is the "Kanto Wanderer" of the title? The yakuza in this movie, including Katsuta, our alleged hero, tend to hang out in the back-alleys of Tokyo. I think the titular wanderer is actually Hanako, played here by Sanae Nakahara, as an eternal imp. Nakahara was a contract player at Nikkatsu, making lots of movies with their biggest stars, including Yujiro Ishihara, and later Jo Shishido and Tetsuya Watari (she's in the purportedly awful sequel to Tokyo Drifter). For Suzuki she is in this film and Smashing the 0-Line. Probably the other most noteworthy films she did at Nikkatsu, besides Kanto Wanderer, were Red Pier, with Yujiro Ishihara, and Farewell to Southern Tosa, also starring Akira Kobayashi. Later she moves on to make a lot of movies with Kinji Fukasaku (she is in a couple of the Battles Without Honor and Humanity movies), and she is in two Tai Kato movies. She is probably the most memorable murder victim in I, the Executioner (she's Keiko, the bourgeois one with the short-cropped hair, I believe), and she plays the main female role in By a Man's Face You Shall Know Him (though the fact that I can't remember her character at all says something about how important a role it probably is). Hanako is the peripatetic driver of Kanto Wanderer's fractured plot, and when the yakuza do leave Tokyo it's to try and find her. The screengrabs constantly remind me how well she plays this role. Suzuki is known to have preferred these very physical performances, and Nakahara plays the part with a lot of different registers of physicality. You can tell when Hanako is playing a role for someone else––in fact, she's always playing a role, and I think it's to Nakahara's credit that she is able to convey not so much a central logic to the character as the implication that there is, somewhere, a central logic to the way Hanako makes decisions. From the outside, she is a very amusing chaos gremlin.

Here is the famous scene, where hipper critics and fans started to take note of Suzuki. I think it looks great in both versions. Interestingly, this was also an alternate take in the trailer.

So Daizaburo Hirata here, playing Diamond Fuyu, calls to attention that Kanto Wanderer is, in fact, a remake, of a film called Song of the Underworld. Both movies are taken from the same novel. Song of the Underworld is a black-and-white Nikkatsu Akushon picture, starring Yujiro Ishihara. It was directed by Suzuki's mentor, Hiroshi Noguchi, who was at the time pioneering a kind of Japanese answer to film noir which was at the time called "Hado-Boirudo"--a phrase adopted from the English-language "hard-boiled." Suzuki was, in fact, Noguchi's assistant director on the previous film. Suzuki was told by his producer that was why he was chosen to direct the remake, though in one of the two Enlglish-language books on Suzuki that came out this year, either Peter Yacavone's or William Carroll's, it was suggested that Akira Kobayashi requested Suzuki for the project, remembering him fondly from their work a few years before on The Boy Who Came Back and Blue Breasts.

It's hard to see Song of the Underworld––I could only find the first five minutes of it online (though in Japan you can stream it through Amazon Prime). But it seems to be a significantly different kind of movie, and this is obvious when you consider that Ishihara in the original film didn't play Katsuta, but actually played Diamond Fuyu as the lead character. The movie seems to be completely different if cast from Diamond Fuyu's point of view. Ishihara was still playing rough young men at the time, and the story from Fuyu's eyes is one of a sort of introduction into the yakuza, and a romantic tragedy. Hiroshi Nawa plays the character that Akira Kobayashi plays in Kanto Wanderer, as a supporting character––sort of a romantic model for the Ishihara character who is more ensconced within the gang structure. Nawa's character's lost love is a subplot in Song of the Underworld, rather than the plot which supercedes the main story in Kanto Wanderer. At the time Kanto Wanderer came out, Toei's yakuza movies were starting to dominate the box office, and Kanto Wanderer was one of Nikkatsu's early forays into the yakuza genre, recasting an earlier teen-action-movie hit as a gangster film. It's very interesting what happens to the Fuyu character in that transition––he becomes, in Suzuki's and the screenwriter's eyes, an absolute loser, mocked at every turn for not being able to fit into the gang structure he so obviously admires. Of course, Suzuki also seems to despise Katsuta, the yakuza hero of the movie––who far more effectively embodies the yakuza ethos. There aren't really that many characters in this movie who escape mockery.

In the program for the first Suzuki retrospective in Europe there is an essay Suzuki wrote about the filming of Kanto Wanderer. He recalls that he offered up several actresses to play Tatsuko, Katsuta's long-lost lover––and the studio shot them down. The day before filming commenced, art director Takeo Kimura suggested Hiroko Ito. "I liked her long face," says Suzuki, "and I've had to reconcile myself to her sweet, nasal voice." This actress has always seemed a little bit unexpected in this role, but the truth is I've found her really attractive in this ineffable way. Apparently she is the love interest of the younger brother in Tattooed Life, as well––and the IMDB lists her as a maid in Kagero-za––which I really must have missed. She has had a strange movie career––only 14 films on imdb––though her career spans from 1957 to 2016. Apparently she is the entomologist's wife in Woman in the Dunes––another role of hers I absolutely do not remember.

There are also a number of shots in the trailer which don't appear in the final film, and it looks like in several cases these would have expanded what had been much smaller roles in the completed film:

This guy! The old-school crime boss from Youth in the Beast. He didn't really feature in Kanto Wanderer much, though he gets a credit line in the trailer.

Boss Yoshida here apparently had at least one more scene. It's really hard to make much sense of this guy in the finished film––he is Fuyu's boss, and he's nominally at odds with Katsuta's boss, Izu, for most of the film. But he doesn't really appear until the end of the movie, when Katsuta intimidates him and then he gets Fuyu to kill Katsuta's boss. I might have liked to see him earlier on, but there is something to how dizzying and diffuse the plot of Kanto Wanderer is when he is withheld until the end.

Now some more caps from the feature. Kanto Wanderer has such extraordinary compositions in it, they always blow my mind:

I love this last image of Katsuta, alone with his unimpeachable honor. Suzuki plays up his haughty isolation so splendidly. If there was any doubt this film was a comedy, I think this last shot makes it very clear how silly Suzuki finds the giri/ninjo conflict, and what little regard he has for these gangsters and their pride.

The Suzuki-gumi were, for my money, the most sophisticated location scouts at Nikkatsu, and Kanto Wanderer is the movie where the locations become a co-star of the picture. Everything seems to be some sort of back-alley or side-view; and in effect, the characters live a back-alley existence, a fully distinct society, grown around the margins of the actual one. The actual society the film depicts is modern for the film's time, but for the gangsters, it's like they're still living in the Taisho era.

My favorite setting. What is this place? It's like some old neighborhood, butted-up against some nondescript hills. Here Noro Keisuke's character is setting up Hanako and planning to sell her.

This shot struck me when seeing the theatrical presentation––the detail in the shadow of the building was profound. I can't say the blu ray renders it with the exquisite sensitivity of the 35mm version, but the shot looks so very much better than it did on DVD. On DVD this shot looked very unremarkable.

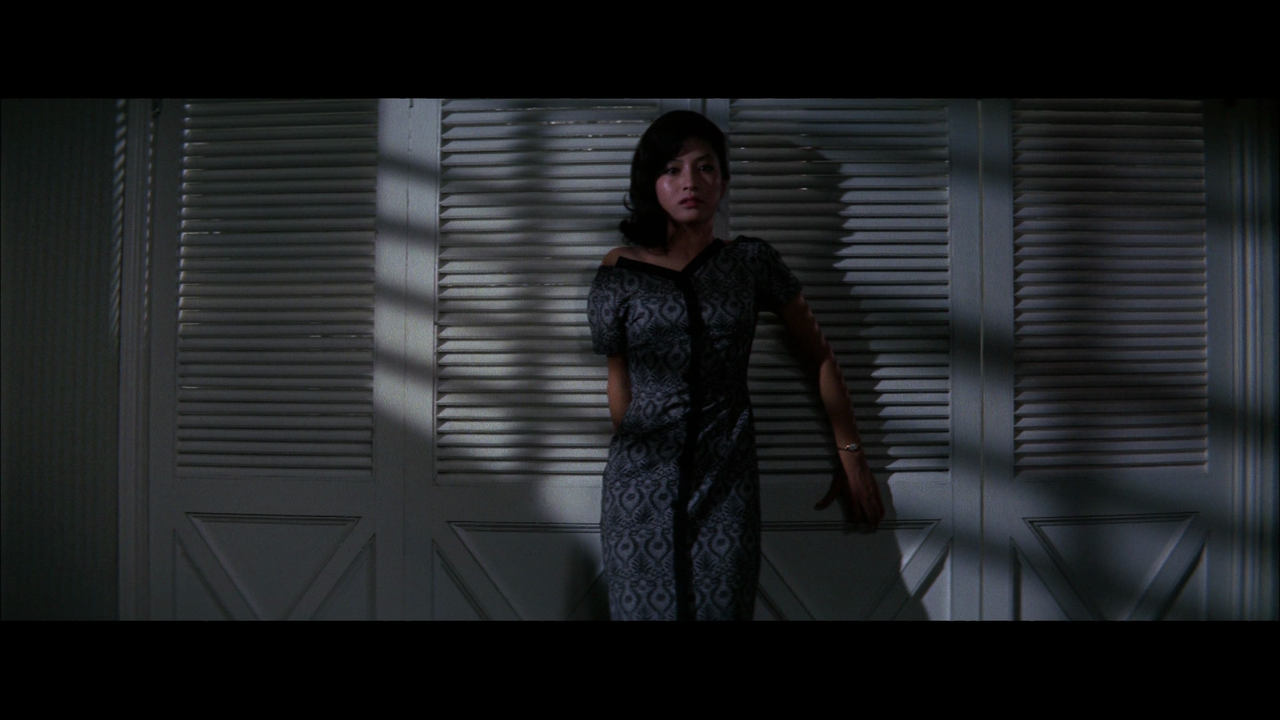

This shot is where I felt I began to "get" Kanto Wanderer, where I began to realize that the film is a magnificently casual paean to procrastination. The way the story works is that Katsuta's underling sells Hanako, Boss Izu's daughter's friend, into prostitution. To make it right, Katsuta and his underling head off to this city, where the underling took Hanako to be sold. Only the underling can't remember where he sold her. This shot intervenes, with Katsuta and his underling leaning against a bridge––the town on one side, spilling over with people engaged in a festival. The two of them mope around as the shot holds. On the other side is the river, adventure, the wild. They begin to realize they'll never find Hanako in the city. Foiled, Katsuta goes to visit Diamond Fuyu, lowly member of a rival gang, who considers himself cuckolded in the selling of Hanako. The idea is that maybe Katsuta can get his clan out of hot water with a direct apology. But Fuyu isn't home. Instead, Katsuta finds Fuyu's sister, and realizes with a shock–––why, it's the long-lost love of Katsuta's life! The woman he endured his prominent scar for! Here she was the whole time, just a couple degrees of separation away. But, what's that? She's married? To a famous gambler? But she still loves Katsuta? Maybe he can beat the gambler. And like that, the film digresses mightily, Katsuta ventures into a dream world, where he may or may not rape Tatsuko––or maybe it's his boss's daughter that he molests? Katsuta can't be sure. Things go from bad to worse for Katsuta's diminutive, pathetic yakuza clan. There are only three of them in the clan, counting the boss. They are facing extinction, and the problem of Fuyu and Hanako threatens the clan's future. Katsuta's boss is too old and greedy and checked-out to do much. Katsuta's underling sucks, and is the reason all this has gone wrong.

I figure, Katsuta knows from the very beginning that it's on him to make some bold, violent, honorable gesture to redeem his clan. Right away in the beginning we see his boss's poetic edict, that the yakuza will end up wearing prison clothes or funeral clothes; Katsuta is devoted to the yakuza life––maybe the only gangster in the film who takes what he's doing seriously. But ultimately, he ends up putting off the sacrifice that is expected of him, almost the entire runtime of the movie. Katsuta hems and haws, going through the motions to maintain the status of the gang; he is alert to any possible distraction, eventually becoming embroiled in an incredibly byzantine romantic entanglement––all to avoid, I think, facing his fate and redeeming his clan. At the end, he does the deed, and goes to prison––resolving his romantic conflict and absurdly clutching on to his meaningless honor (his boss is dead, extinguishing his clan anyway) as he prepares for decades in prison––a dinosaur of traditions Suzuki seems to be saying are not only outmoded, but were always bullsh*t to begin with. Meanwhile, Hanako, the titular wanderer of the Kanto plain, climbs higher and higher within the yakuza structure, never becoming cornered like Tatsuko, never being disrespected, like Fuyu, and never being forced to enact a fate like Katsuta's. She can move so seamlessly through the yakuza system because she thinks of it all as amusing, faintly ridiculous, and not worth getting caught up in. Hanako's mobility is liberating to the viewer, and anarchic, too––all this trouble, after all, is due to her cheeky curiosity and daring, and she doesn't really care. One imagines if any of the mobbed-up characters in the movie understood what Hanako had done, they would be horrified by the way she steps upon their sense of tradition and their own sense of importance.

Suzuki handles the themes of this movie so very deftly. This thread is a consistent visual motif, marking the boundary between the world of the yakuza and the larger society. Here a detective stands at the foot of the stairs leading up to the gambling den where Katsuta and Tatsuko's husband are squaring off. Does the detective actually see the thread? Is it real? Later on, when Katsuta pleads with his boss, the thread vibrates right in front of the camera lens. This effect is plain to see in the theater, but was very obscured on dvd. The blu ray makes it easy to perceive.

Lastly, Suzuki isn't Von Sterberg (though Yacavone goes into a striking comparison of the von Sternberg Dietrich movies and Suzuki's Flesh Trilogy), but god-damn, is this film filled with really exquisite close-ups:

Apparently Kobayashi chose to have his eyebrows made up extra-thick for the film. According to Suzuki, he took the blame when the studio disliked the choice, though he tried to convince the executives Kobayashi had insisted upon it

Katsuta enters the Taisho-styled dream world in the midst of Kanto Wanderer. This is Suzuki's first movie to feature to utilize dream in order to evoke a level of narrative ambiguity––there are dreamlike moments in earlier pictures, like Passport to Darkness and Nude Girl with a Gun, and in the later Story of a Prostitute, but those isolated shots or sequences are mostly revealed to be real, or the demarcation between dream and reality is much clearer. Kanto Wanderer first presents us with the kind of ambiguous sequences which run between suggestive dream and possible erotic reality––something we'll see again in Branded to Kill, a little bit in A Mummy's Love, Fang in the Hole, and Story of Sorrow and Sadness, and then emerging full-force in the Taisho Trilogy movies and in Suzuki's early video project, Cherry Blossoms in Spring. As in Zigeunerweisen, the passage into the dream world is marked by non-diegetic lighting choices––here an eery blue light contrasting with the yellow of the street light.

Chieko Matsubara was often paired with Akira Kobayashi around this time. She is always treated as a sort of virginal beauty in these films, but as a person she comes across as an absolute workhorse actress. She has 170 credits on the IMDB, 100 of which were made at Nikkatsu. She has never really impressed me in these movies, though she never exactly disappoints. But I think her particular look and presence always seems a little vague. Suzuki makes the best of this, normally. In the four films she makes with him, he most frequently casts her as someone who is sort of "out of it," a character walking a different path, outside of the main milieu of the story. In Tokyo Drifter she plays a character so remote from the rest of the movie her boyfriend would rather take to the open road than be with her. In The Flower and the Angry Waves she is the secret wife Kobayashi's character keeps hidden away, who can never really be part of his world, the way the prostitute, Manryu can be (and in that film, Manryu seems a more deserving love interest for Kobayashi's character). Our Blood Will Not Forgive is the outlier in this group of movies, where she is almost unrecognizable playing Kobayashi's mobbed-up girlfriend. This is her least-believable role in a Suzuki film. In Kanto Wanderer, she is the boss's daughter, and Suzuki really underlines how disengaged from the yakuza drama she is. She has a vague crush on Katsuta, but is also shown mocking his seriousness, playing in piles of leaves, and clowning around in schoolgirl fashion. When she tries to romance Katsuta, he appears to rape her, half-dreaming and believing she is actually his love, Tatsuko. She disappears from the movie after this, presumably deciding she doesn't want any more to do with these filthy yakuza. I think she comes across as most animate in this film and in Flower and the Angry Waves. In Tokyo Drifter she is kind of the hero's unwitting "beard."

Here's a tiny bit of damage on the feature. This hardly happens; the film looks exceptionally clean of the kind of scratches and debris you see on many of the other transfers in these sets.

Here are my comparisons to the trailer. Another note needs be added here for the comparisons––as with Fighting Elegy, it was impossible to match most of the captures exactly, because the trailer uses a lot of alternate takes of shots. In terms of Kanto Wanderer, virtually every shot was an alternate, with subtle adjustments to camera position and with the actors delivering different timing.

This persists throughout the comparison. The saturation of colors on the feature is much closer to what was presented when I saw the film in 35mm. In fact, all of Suzuki's color films from Nikkatsu which I've seen in 35mm have at least this saturated a color scheme (I haven't seen a lot of the more muted–seeming color films in 35mm––neither of the boxing movies, for example, or A Hell of a Guy, which seems to have a strong blue/yellow bias––but I did see Our Blood Will Not Forgive, which is more muted and blue than the other films of this era, and the more blue-and-grey color palette of that film was still quite saturated. There were some differences between the films with Shigeyoshi Mine as cinematographer––which tended to foreground these big panels of saturated color––and the ones where Kazue Nagatsuka shot them––he tended to highlight smaller, more subtle color expressions––and then there was some difference with films shot by other cinematographers, like Tattooed Life and Story of Sorrow and Sadness). To my eyes, the feature has much more depth-of-field here––maybe partly due to the broader range of contrast present in the feature transfer.

Who is the "Kanto Wanderer" of the title? The yakuza in this movie, including Katsuta, our alleged hero, tend to hang out in the back-alleys of Tokyo. I think the titular wanderer is actually Hanako, played here by Sanae Nakahara, as an eternal imp. Nakahara was a contract player at Nikkatsu, making lots of movies with their biggest stars, including Yujiro Ishihara, and later Jo Shishido and Tetsuya Watari (she's in the purportedly awful sequel to Tokyo Drifter). For Suzuki she is in this film and Smashing the 0-Line. Probably the other most noteworthy films she did at Nikkatsu, besides Kanto Wanderer, were Red Pier, with Yujiro Ishihara, and Farewell to Southern Tosa, also starring Akira Kobayashi. Later she moves on to make a lot of movies with Kinji Fukasaku (she is in a couple of the Battles Without Honor and Humanity movies), and she is in two Tai Kato movies. She is probably the most memorable murder victim in I, the Executioner (she's Keiko, the bourgeois one with the short-cropped hair, I believe), and she plays the main female role in By a Man's Face You Shall Know Him (though the fact that I can't remember her character at all says something about how important a role it probably is). Hanako is the peripatetic driver of Kanto Wanderer's fractured plot, and when the yakuza do leave Tokyo it's to try and find her. The screengrabs constantly remind me how well she plays this role. Suzuki is known to have preferred these very physical performances, and Nakahara plays the part with a lot of different registers of physicality. You can tell when Hanako is playing a role for someone else––in fact, she's always playing a role, and I think it's to Nakahara's credit that she is able to convey not so much a central logic to the character as the implication that there is, somewhere, a central logic to the way Hanako makes decisions. From the outside, she is a very amusing chaos gremlin.

Here is the famous scene, where hipper critics and fans started to take note of Suzuki. I think it looks great in both versions. Interestingly, this was also an alternate take in the trailer.

So Daizaburo Hirata here, playing Diamond Fuyu, calls to attention that Kanto Wanderer is, in fact, a remake, of a film called Song of the Underworld. Both movies are taken from the same novel. Song of the Underworld is a black-and-white Nikkatsu Akushon picture, starring Yujiro Ishihara. It was directed by Suzuki's mentor, Hiroshi Noguchi, who was at the time pioneering a kind of Japanese answer to film noir which was at the time called "Hado-Boirudo"--a phrase adopted from the English-language "hard-boiled." Suzuki was, in fact, Noguchi's assistant director on the previous film. Suzuki was told by his producer that was why he was chosen to direct the remake, though in one of the two Enlglish-language books on Suzuki that came out this year, either Peter Yacavone's or William Carroll's, it was suggested that Akira Kobayashi requested Suzuki for the project, remembering him fondly from their work a few years before on The Boy Who Came Back and Blue Breasts.

It's hard to see Song of the Underworld––I could only find the first five minutes of it online (though in Japan you can stream it through Amazon Prime). But it seems to be a significantly different kind of movie, and this is obvious when you consider that Ishihara in the original film didn't play Katsuta, but actually played Diamond Fuyu as the lead character. The movie seems to be completely different if cast from Diamond Fuyu's point of view. Ishihara was still playing rough young men at the time, and the story from Fuyu's eyes is one of a sort of introduction into the yakuza, and a romantic tragedy. Hiroshi Nawa plays the character that Akira Kobayashi plays in Kanto Wanderer, as a supporting character––sort of a romantic model for the Ishihara character who is more ensconced within the gang structure. Nawa's character's lost love is a subplot in Song of the Underworld, rather than the plot which supercedes the main story in Kanto Wanderer. At the time Kanto Wanderer came out, Toei's yakuza movies were starting to dominate the box office, and Kanto Wanderer was one of Nikkatsu's early forays into the yakuza genre, recasting an earlier teen-action-movie hit as a gangster film. It's very interesting what happens to the Fuyu character in that transition––he becomes, in Suzuki's and the screenwriter's eyes, an absolute loser, mocked at every turn for not being able to fit into the gang structure he so obviously admires. Of course, Suzuki also seems to despise Katsuta, the yakuza hero of the movie––who far more effectively embodies the yakuza ethos. There aren't really that many characters in this movie who escape mockery.

In the program for the first Suzuki retrospective in Europe there is an essay Suzuki wrote about the filming of Kanto Wanderer. He recalls that he offered up several actresses to play Tatsuko, Katsuta's long-lost lover––and the studio shot them down. The day before filming commenced, art director Takeo Kimura suggested Hiroko Ito. "I liked her long face," says Suzuki, "and I've had to reconcile myself to her sweet, nasal voice." This actress has always seemed a little bit unexpected in this role, but the truth is I've found her really attractive in this ineffable way. Apparently she is the love interest of the younger brother in Tattooed Life, as well––and the IMDB lists her as a maid in Kagero-za––which I really must have missed. She has had a strange movie career––only 14 films on imdb––though her career spans from 1957 to 2016. Apparently she is the entomologist's wife in Woman in the Dunes––another role of hers I absolutely do not remember.

There are also a number of shots in the trailer which don't appear in the final film, and it looks like in several cases these would have expanded what had been much smaller roles in the completed film:

This guy! The old-school crime boss from Youth in the Beast. He didn't really feature in Kanto Wanderer much, though he gets a credit line in the trailer.

Boss Yoshida here apparently had at least one more scene. It's really hard to make much sense of this guy in the finished film––he is Fuyu's boss, and he's nominally at odds with Katsuta's boss, Izu, for most of the film. But he doesn't really appear until the end of the movie, when Katsuta intimidates him and then he gets Fuyu to kill Katsuta's boss. I might have liked to see him earlier on, but there is something to how dizzying and diffuse the plot of Kanto Wanderer is when he is withheld until the end.

Now some more caps from the feature. Kanto Wanderer has such extraordinary compositions in it, they always blow my mind:

I love this last image of Katsuta, alone with his unimpeachable honor. Suzuki plays up his haughty isolation so splendidly. If there was any doubt this film was a comedy, I think this last shot makes it very clear how silly Suzuki finds the giri/ninjo conflict, and what little regard he has for these gangsters and their pride.

The Suzuki-gumi were, for my money, the most sophisticated location scouts at Nikkatsu, and Kanto Wanderer is the movie where the locations become a co-star of the picture. Everything seems to be some sort of back-alley or side-view; and in effect, the characters live a back-alley existence, a fully distinct society, grown around the margins of the actual one. The actual society the film depicts is modern for the film's time, but for the gangsters, it's like they're still living in the Taisho era.

My favorite setting. What is this place? It's like some old neighborhood, butted-up against some nondescript hills. Here Noro Keisuke's character is setting up Hanako and planning to sell her.

This shot struck me when seeing the theatrical presentation––the detail in the shadow of the building was profound. I can't say the blu ray renders it with the exquisite sensitivity of the 35mm version, but the shot looks so very much better than it did on DVD. On DVD this shot looked very unremarkable.

This shot is where I felt I began to "get" Kanto Wanderer, where I began to realize that the film is a magnificently casual paean to procrastination. The way the story works is that Katsuta's underling sells Hanako, Boss Izu's daughter's friend, into prostitution. To make it right, Katsuta and his underling head off to this city, where the underling took Hanako to be sold. Only the underling can't remember where he sold her. This shot intervenes, with Katsuta and his underling leaning against a bridge––the town on one side, spilling over with people engaged in a festival. The two of them mope around as the shot holds. On the other side is the river, adventure, the wild. They begin to realize they'll never find Hanako in the city. Foiled, Katsuta goes to visit Diamond Fuyu, lowly member of a rival gang, who considers himself cuckolded in the selling of Hanako. The idea is that maybe Katsuta can get his clan out of hot water with a direct apology. But Fuyu isn't home. Instead, Katsuta finds Fuyu's sister, and realizes with a shock–––why, it's the long-lost love of Katsuta's life! The woman he endured his prominent scar for! Here she was the whole time, just a couple degrees of separation away. But, what's that? She's married? To a famous gambler? But she still loves Katsuta? Maybe he can beat the gambler. And like that, the film digresses mightily, Katsuta ventures into a dream world, where he may or may not rape Tatsuko––or maybe it's his boss's daughter that he molests? Katsuta can't be sure. Things go from bad to worse for Katsuta's diminutive, pathetic yakuza clan. There are only three of them in the clan, counting the boss. They are facing extinction, and the problem of Fuyu and Hanako threatens the clan's future. Katsuta's boss is too old and greedy and checked-out to do much. Katsuta's underling sucks, and is the reason all this has gone wrong.

I figure, Katsuta knows from the very beginning that it's on him to make some bold, violent, honorable gesture to redeem his clan. Right away in the beginning we see his boss's poetic edict, that the yakuza will end up wearing prison clothes or funeral clothes; Katsuta is devoted to the yakuza life––maybe the only gangster in the film who takes what he's doing seriously. But ultimately, he ends up putting off the sacrifice that is expected of him, almost the entire runtime of the movie. Katsuta hems and haws, going through the motions to maintain the status of the gang; he is alert to any possible distraction, eventually becoming embroiled in an incredibly byzantine romantic entanglement––all to avoid, I think, facing his fate and redeeming his clan. At the end, he does the deed, and goes to prison––resolving his romantic conflict and absurdly clutching on to his meaningless honor (his boss is dead, extinguishing his clan anyway) as he prepares for decades in prison––a dinosaur of traditions Suzuki seems to be saying are not only outmoded, but were always bullsh*t to begin with. Meanwhile, Hanako, the titular wanderer of the Kanto plain, climbs higher and higher within the yakuza structure, never becoming cornered like Tatsuko, never being disrespected, like Fuyu, and never being forced to enact a fate like Katsuta's. She can move so seamlessly through the yakuza system because she thinks of it all as amusing, faintly ridiculous, and not worth getting caught up in. Hanako's mobility is liberating to the viewer, and anarchic, too––all this trouble, after all, is due to her cheeky curiosity and daring, and she doesn't really care. One imagines if any of the mobbed-up characters in the movie understood what Hanako had done, they would be horrified by the way she steps upon their sense of tradition and their own sense of importance.

Suzuki handles the themes of this movie so very deftly. This thread is a consistent visual motif, marking the boundary between the world of the yakuza and the larger society. Here a detective stands at the foot of the stairs leading up to the gambling den where Katsuta and Tatsuko's husband are squaring off. Does the detective actually see the thread? Is it real? Later on, when Katsuta pleads with his boss, the thread vibrates right in front of the camera lens. This effect is plain to see in the theater, but was very obscured on dvd. The blu ray makes it easy to perceive.

Lastly, Suzuki isn't Von Sterberg (though Yacavone goes into a striking comparison of the von Sternberg Dietrich movies and Suzuki's Flesh Trilogy), but god-damn, is this film filled with really exquisite close-ups:

Apparently Kobayashi chose to have his eyebrows made up extra-thick for the film. According to Suzuki, he took the blame when the studio disliked the choice, though he tried to convince the executives Kobayashi had insisted upon it

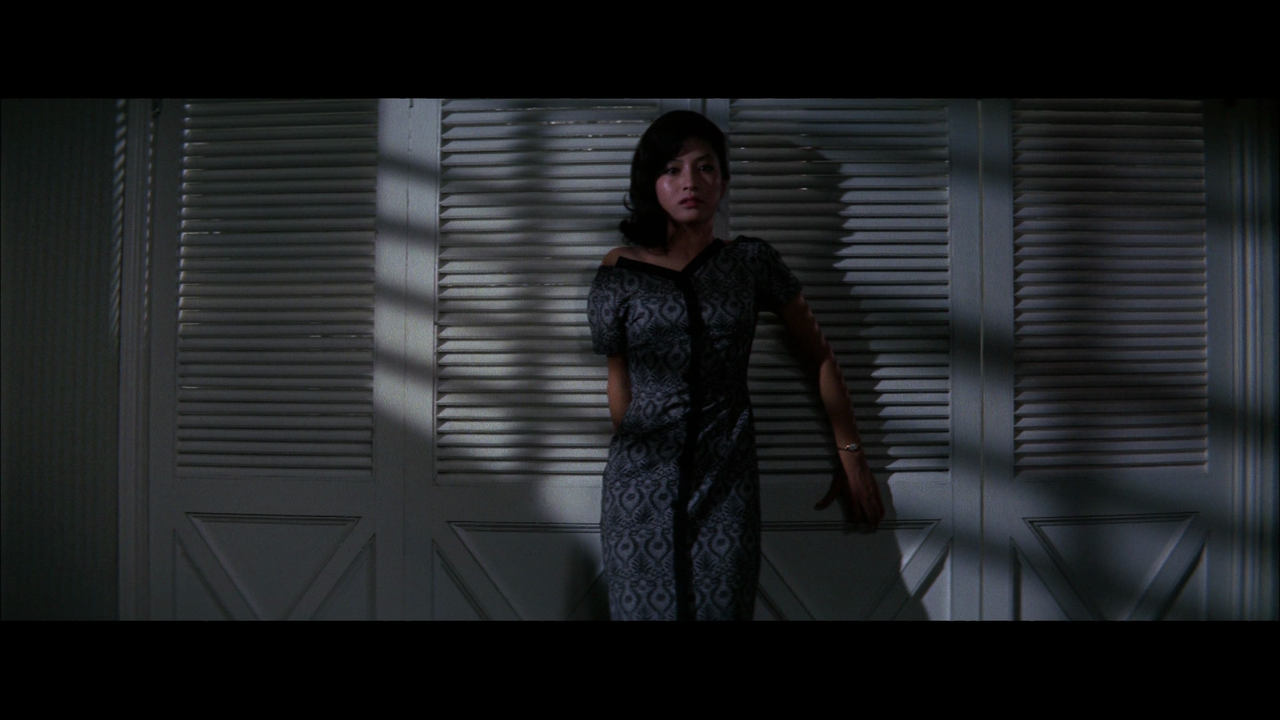

Katsuta enters the Taisho-styled dream world in the midst of Kanto Wanderer. This is Suzuki's first movie to feature to utilize dream in order to evoke a level of narrative ambiguity––there are dreamlike moments in earlier pictures, like Passport to Darkness and Nude Girl with a Gun, and in the later Story of a Prostitute, but those isolated shots or sequences are mostly revealed to be real, or the demarcation between dream and reality is much clearer. Kanto Wanderer first presents us with the kind of ambiguous sequences which run between suggestive dream and possible erotic reality––something we'll see again in Branded to Kill, a little bit in A Mummy's Love, Fang in the Hole, and Story of Sorrow and Sadness, and then emerging full-force in the Taisho Trilogy movies and in Suzuki's early video project, Cherry Blossoms in Spring. As in Zigeunerweisen, the passage into the dream world is marked by non-diegetic lighting choices––here an eery blue light contrasting with the yellow of the street light.

Chieko Matsubara was often paired with Akira Kobayashi around this time. She is always treated as a sort of virginal beauty in these films, but as a person she comes across as an absolute workhorse actress. She has 170 credits on the IMDB, 100 of which were made at Nikkatsu. She has never really impressed me in these movies, though she never exactly disappoints. But I think her particular look and presence always seems a little vague. Suzuki makes the best of this, normally. In the four films she makes with him, he most frequently casts her as someone who is sort of "out of it," a character walking a different path, outside of the main milieu of the story. In Tokyo Drifter she plays a character so remote from the rest of the movie her boyfriend would rather take to the open road than be with her. In The Flower and the Angry Waves she is the secret wife Kobayashi's character keeps hidden away, who can never really be part of his world, the way the prostitute, Manryu can be (and in that film, Manryu seems a more deserving love interest for Kobayashi's character). Our Blood Will Not Forgive is the outlier in this group of movies, where she is almost unrecognizable playing Kobayashi's mobbed-up girlfriend. This is her least-believable role in a Suzuki film. In Kanto Wanderer, she is the boss's daughter, and Suzuki really underlines how disengaged from the yakuza drama she is. She has a vague crush on Katsuta, but is also shown mocking his seriousness, playing in piles of leaves, and clowning around in schoolgirl fashion. When she tries to romance Katsuta, he appears to rape her, half-dreaming and believing she is actually his love, Tatsuko. She disappears from the movie after this, presumably deciding she doesn't want any more to do with these filthy yakuza. I think she comes across as most animate in this film and in Flower and the Angry Waves. In Tokyo Drifter she is kind of the hero's unwitting "beard."

Here's a tiny bit of damage on the feature. This hardly happens; the film looks exceptionally clean of the kind of scratches and debris you see on many of the other transfers in these sets.

SpoilerShow

The disc scans like the other non-4k scans in these collections, as 1080i, with a 1080p trailer attached. In those cases on the previous set, Seijun on Men, the result was pretty clear across the board––in each case, the trailer had a sharper image, with more depth, and things like movement looked more dynamic overall. Kanto Wanderer, however is quite different. For starters, the trailer seems more damaged than those on the other films. But secondly, the feature on this disc looks great, in spite of technical limitations. Perhaps because previous versions were quite poor, I'm weighting it more favorably. But this is one of the discs in the set where the feature looks most special. Color and contrast are improved from the trailer, but there is also a cleaner grain structure, which looks finer to me. While it's playing, the feature has a lot of depth and visual sophistication. It isn't as sharp as the 4k transfers, to be sure, but it looks beautiful all the same.

Here are my comparisons to the trailer. Another note needs be added here for the comparisons––as with Fighting Elegy, it was impossible to match most of the captures exactly, because the trailer uses a lot of alternate takes of shots. In terms of Kanto Wanderer, virtually every shot was an alternate, with subtle adjustments to camera position and with the actors delivering different timing.

Trailer

Feature

You can see right away that the trailer is softer and that the colors frequently bleed.

Trailer

Feature

This persists throughout the comparison. The saturation of colors on the feature is much closer to what was presented when I saw the film in 35mm. In fact, all of Suzuki's color films from Nikkatsu which I've seen in 35mm have at least this saturated a color scheme (I haven't seen a lot of the more muted–seeming color films in 35mm––neither of the boxing movies, for example, or A Hell of a Guy, which seems to have a strong blue/yellow bias––but I did see Our Blood Will Not Forgive, which is more muted and blue than the other films of this era, and the more blue-and-grey color palette of that film was still quite saturated. There were some differences between the films with Shigeyoshi Mine as cinematographer––which tended to foreground these big panels of saturated color––and the ones where Kazue Nagatsuka shot them––he tended to highlight smaller, more subtle color expressions––and then there was some difference with films shot by other cinematographers, like Tattooed Life and Story of Sorrow and Sadness). To my eyes, the feature has much more depth-of-field here––maybe partly due to the broader range of contrast present in the feature transfer.

Trailer

Feature

Who is the "Kanto Wanderer" of the title? The yakuza in this movie, including Katsuta, our alleged hero, tend to hang out in the back-alleys of Tokyo. I think the titular wanderer is actually Hanako, played here by Sanae Nakahara, as an eternal imp. Nakahara was a contract player at Nikkatsu, making lots of movies with their biggest stars, including Yujiro Ishihara, and later Jo Shishido and Tetsuya Watari (she's in the purportedly awful sequel to Tokyo Drifter). For Suzuki she is in this film and Smashing the 0-Line. Probably the other most noteworthy films she did at Nikkatsu, besides Kanto Wanderer, were Red Pier, with Yujiro Ishihara, and Farewell to Southern Tosa, also starring Akira Kobayashi. Later she moves on to make a lot of movies with Kinji Fukasaku (she is in a couple of the Battles Without Honor and Humanity movies), and she is in two Tai Kato movies. She is probably the most memorable murder victim in I, the Executioner (she's Keiko, the bourgeois one with the short-cropped hair, I believe), and she plays the main female role in By a Man's Face You Shall Know Him (though the fact that I can't remember her character at all says something about how important a role it probably is). Hanako is the peripatetic driver of Kanto Wanderer's fractured plot, and when the yakuza do leave Tokyo it's to try and find her. The screengrabs constantly remind me how well she plays this role. Suzuki is known to have preferred these very physical performances, and Nakahara plays the part with a lot of different registers of physicality. You can tell when Hanako is playing a role for someone else––in fact, she's always playing a role, and I think it's to Nakahara's credit that she is able to convey not so much a central logic to the character as the implication that there is, somewhere, a central logic to the way Hanako makes decisions. From the outside, she is a very amusing chaos gremlin.

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Trailer

Feature

Here is the famous scene, where hipper critics and fans started to take note of Suzuki. I think it looks great in both versions. Interestingly, this was also an alternate take in the trailer.

Trailer

Feature

So Daizaburo Hirata here, playing Diamond Fuyu, calls to attention that Kanto Wanderer is, in fact, a remake, of a film called Song of the Underworld. Both movies are taken from the same novel. Song of the Underworld is a black-and-white Nikkatsu Akushon picture, starring Yujiro Ishihara. It was directed by Suzuki's mentor, Hiroshi Noguchi, who was at the time pioneering a kind of Japanese answer to film noir which was at the time called "Hado-Boirudo"--a phrase adopted from the English-language "hard-boiled." Suzuki was, in fact, Noguchi's assistant director on the previous film. Suzuki was told by his producer that was why he was chosen to direct the remake, though in one of the two Enlglish-language books on Suzuki that came out this year, either Peter Yacavone's or William Carroll's, it was suggested that Akira Kobayashi requested Suzuki for the project, remembering him fondly from their work a few years before on The Boy Who Came Back and Blue Breasts.

It's hard to see Song of the Underworld––I could only find the first five minutes of it online (though in Japan you can stream it through Amazon Prime). But it seems to be a significantly different kind of movie, and this is obvious when you consider that Ishihara in the original film didn't play Katsuta, but actually played Diamond Fuyu as the lead character. The movie seems to be completely different if cast from Diamond Fuyu's point of view. Ishihara was still playing rough young men at the time, and the story from Fuyu's eyes is one of a sort of introduction into the yakuza, and a romantic tragedy. Hiroshi Nawa plays the character that Akira Kobayashi plays in Kanto Wanderer, as a supporting character––sort of a romantic model for the Ishihara character who is more ensconced within the gang structure. Nawa's character's lost love is a subplot in Song of the Underworld, rather than the plot which supercedes the main story in Kanto Wanderer. At the time Kanto Wanderer came out, Toei's yakuza movies were starting to dominate the box office, and Kanto Wanderer was one of Nikkatsu's early forays into the yakuza genre, recasting an earlier teen-action-movie hit as a gangster film. It's very interesting what happens to the Fuyu character in that transition––he becomes, in Suzuki's and the screenwriter's eyes, an absolute loser, mocked at every turn for not being able to fit into the gang structure he so obviously admires. Of course, Suzuki also seems to despise Katsuta, the yakuza hero of the movie––who far more effectively embodies the yakuza ethos. There aren't really that many characters in this movie who escape mockery.

Trailer

Feature

In the program for the first Suzuki retrospective in Europe there is an essay Suzuki wrote about the filming of Kanto Wanderer. He recalls that he offered up several actresses to play Tatsuko, Katsuta's long-lost lover––and the studio shot them down. The day before filming commenced, art director Takeo Kimura suggested Hiroko Ito. "I liked her long face," says Suzuki, "and I've had to reconcile myself to her sweet, nasal voice." This actress has always seemed a little bit unexpected in this role, but the truth is I've found her really attractive in this ineffable way. Apparently she is the love interest of the younger brother in Tattooed Life, as well––and the IMDB lists her as a maid in Kagero-za––which I really must have missed. She has had a strange movie career––only 14 films on imdb––though her career spans from 1957 to 2016. Apparently she is the entomologist's wife in Woman in the Dunes––another role of hers I absolutely do not remember.

Trailer

Feature

There are also a number of shots in the trailer which don't appear in the final film, and it looks like in several cases these would have expanded what had been much smaller roles in the completed film:

This guy! The old-school crime boss from Youth in the Beast. He didn't really feature in Kanto Wanderer much, though he gets a credit line in the trailer.

Boss Yoshida here apparently had at least one more scene. It's really hard to make much sense of this guy in the finished film––he is Fuyu's boss, and he's nominally at odds with Katsuta's boss, Izu, for most of the film. But he doesn't really appear until the end of the movie, when Katsuta intimidates him and then he gets Fuyu to kill Katsuta's boss. I might have liked to see him earlier on, but there is something to how dizzying and diffuse the plot of Kanto Wanderer is when he is withheld until the end.

Now some more caps from the feature. Kanto Wanderer has such extraordinary compositions in it, they always blow my mind:

I love this last image of Katsuta, alone with his unimpeachable honor. Suzuki plays up his haughty isolation so splendidly. If there was any doubt this film was a comedy, I think this last shot makes it very clear how silly Suzuki finds the giri/ninjo conflict, and what little regard he has for these gangsters and their pride.

The Suzuki-gumi were, for my money, the most sophisticated location scouts at Nikkatsu, and Kanto Wanderer is the movie where the locations become a co-star of the picture. Everything seems to be some sort of back-alley or side-view; and in effect, the characters live a back-alley existence, a fully distinct society, grown around the margins of the actual one. The actual society the film depicts is modern for the film's time, but for the gangsters, it's like they're still living in the Taisho era.

My favorite setting. What is this place? It's like some old neighborhood, butted-up against some nondescript hills. Here Noro Keisuke's character is setting up Hanako and planning to sell her.

This shot struck me when seeing the theatrical presentation––the detail in the shadow of the building was profound. I can't say the blu ray renders it with the exquisite sensitivity of the 35mm version, but the shot looks so very much better than it did on DVD. On DVD this shot looked very unremarkable.

This shot is where I felt I began to "get" Kanto Wanderer, where I began to realize that the film is a magnificently casual paean to procrastination. The way the story works is that Katsuta's underling sells Hanako, Boss Izu's daughter's friend, into prostitution. To make it right, Katsuta and his underling head off to this city, where the underling took Hanako to be sold. Only the underling can't remember where he sold her. This shot intervenes, with Katsuta and his underling leaning against a bridge––the town on one side, spilling over with people engaged in a festival. The two of them mope around as the shot holds. On the other side is the river, adventure, the wild. They begin to realize they'll never find Hanako in the city. Foiled, Katsuta goes to visit Diamond Fuyu, lowly member of a rival gang, who considers himself cuckolded in the selling of Hanako. The idea is that maybe Katsuta can get his clan out of hot water with a direct apology. But Fuyu isn't home. Instead, Katsuta finds Fuyu's sister, and realizes with a shock–––why, it's the long-lost love of Katsuta's life! The woman he endured his prominent scar for! Here she was the whole time, just a couple degrees of separation away. But, what's that? She's married? To a famous gambler? But she still loves Katsuta? Maybe he can beat the gambler. And like that, the film digresses mightily, Katsuta ventures into a dream world, where he may or may not rape Tatsuko––or maybe it's his boss's daughter that he molests? Katsuta can't be sure. Things go from bad to worse for Katsuta's diminutive, pathetic yakuza clan. There are only three of them in the clan, counting the boss. They are facing extinction, and the problem of Fuyu and Hanako threatens the clan's future. Katsuta's boss is too old and greedy and checked-out to do much. Katsuta's underling sucks, and is the reason all this has gone wrong.

I figure, Katsuta knows from the very beginning that it's on him to make some bold, violent, honorable gesture to redeem his clan. Right away in the beginning we see his boss's poetic edict, that the yakuza will end up wearing prison clothes or funeral clothes; Katsuta is devoted to the yakuza life––maybe the only gangster in the film who takes what he's doing seriously. But ultimately, he ends up putting off the sacrifice that is expected of him, almost the entire runtime of the movie. Katsuta hems and haws, going through the motions to maintain the status of the gang; he is alert to any possible distraction, eventually becoming embroiled in an incredibly byzantine romantic entanglement––all to avoid, I think, facing his fate and redeeming his clan. At the end, he does the deed, and goes to prison––resolving his romantic conflict and absurdly clutching on to his meaningless honor (his boss is dead, extinguishing his clan anyway) as he prepares for decades in prison––a dinosaur of traditions Suzuki seems to be saying are not only outmoded, but were always bullsh*t to begin with. Meanwhile, Hanako, the titular wanderer of the Kanto plain, climbs higher and higher within the yakuza structure, never becoming cornered like Tatsuko, never being disrespected, like Fuyu, and never being forced to enact a fate like Katsuta's. She can move so seamlessly through the yakuza system because she thinks of it all as amusing, faintly ridiculous, and not worth getting caught up in. Hanako's mobility is liberating to the viewer, and anarchic, too––all this trouble, after all, is due to her cheeky curiosity and daring, and she doesn't really care. One imagines if any of the mobbed-up characters in the movie understood what Hanako had done, they would be horrified by the way she steps upon their sense of tradition and their own sense of importance.

Suzuki handles the themes of this movie so very deftly. This thread is a consistent visual motif, marking the boundary between the world of the yakuza and the larger society. Here a detective stands at the foot of the stairs leading up to the gambling den where Katsuta and Tatsuko's husband are squaring off. Does the detective actually see the thread? Is it real? Later on, when Katsuta pleads with his boss, the thread vibrates right in front of the camera lens. This effect is plain to see in the theater, but was very obscured on dvd. The blu ray makes it easy to perceive.

Lastly, Suzuki isn't Von Sterberg (though Yacavone goes into a striking comparison of the von Sternberg Dietrich movies and Suzuki's Flesh Trilogy), but god-damn, is this film filled with really exquisite close-ups:

Apparently Kobayashi chose to have his eyebrows made up extra-thick for the film. According to Suzuki, he took the blame when the studio disliked the choice, though he tried to convince the executives Kobayashi had insisted upon it.

Katsuta enters the Taisho-styled dream world in the midst of Kanto Wanderer. This is Suzuki's first movie to feature to utilize dream in order to evoke a level of narrative ambiguity––there are dreamlike moments in earlier pictures, like Passport to Darkness and Nude Girl with a Gun, and in the later Story of a Prostitute, but those isolated shots or sequences are mostly revealed to be real, or the demarcation between dream and reality is much clearer. Kanto Wanderer first presents us with the kind of ambiguous sequences which run between suggestive dream and possible erotic reality––something we'll see again in Branded to Kill, a little bit in A Mummy's Love, Fang in the Hole, and Story of Sorrow and Sadness, and then emerging full-force in the Taisho Trilogy movies and in Suzuki's early video project, Cherry Blossoms in Spring. As in Zigeunerweisen, the passage into the dream world is marked by non-diegetic lighting choices––here an eery blue light contrasting with the yellow of the street light.

Chieko Matsubara was often paired with Akira Kobayashi around this time. She is always treated as a sort of virginal beauty in these films, but as a person she comes across as an absolute workhorse actress. She has 170 credits on the IMDB, 100 of which were made at Nikkatsu. She has never really impressed me in these movies, though she never exactly disappoints. But I think her particular look and presence always seems a little vague. Suzuki makes the best of this, normally. In the four films she makes with him, he most frequently casts her as someone who is sort of "out of it," a character walking a different path, outside of the main milieu of the story. In Tokyo Drifter she plays a character so remote from the rest of the movie her boyfriend would rather take to the open road than be with her. In The Flower and the Angry Waves she is the secret wife Kobayashi's character keeps hidden away, who can never really be part of his world, the way the prostitute, Manryu can be (and in that film, Manryu seems a more deserving love interest for Kobayashi's character). Our Blood Will Not Forgive is the outlier in this group of movies, where she is almost unrecognizable playing Kobayashi's mobbed-up girlfriend. This is her least-believable role in a Suzuki film. In Kanto Wanderer, she is the boss's daughter, and Suzuki really underlines how disengaged from the yakuza drama she is. She has a vague crush on Katsuta, but is also shown mocking his seriousness, playing in piles of leaves, and clowning around in schoolgirl fashion. When she tries to romance Katsuta, he appears to rape her, half-dreaming and believing she is actually his love, Tatsuko. She disappears from the movie after this, presumably deciding she doesn't want any more to do with these filthy yakuza. I think she comes across as most animate in this film and in Flower and the Angry Waves. In Tokyo Drifter she is kind of the hero's unwitting "beard."

Here's a tiny bit of damage on the feature. This hardly happens; the film looks exceptionally clean of the kind of scratches and debris you see on many of the other transfers in these sets.

Here are my comparisons to the trailer. Another note needs be added here for the comparisons––as with Fighting Elegy, it was impossible to match most of the captures exactly, because the trailer uses a lot of alternate takes of shots. In terms of Kanto Wanderer, virtually every shot was an alternate, with subtle adjustments to camera position and with the actors delivering different timing.

Trailer

Feature

You can see right away that the trailer is softer and that the colors frequently bleed.

Trailer

Feature

This persists throughout the comparison. The saturation of colors on the feature is much closer to what was presented when I saw the film in 35mm. In fact, all of Suzuki's color films from Nikkatsu which I've seen in 35mm have at least this saturated a color scheme (I haven't seen a lot of the more muted–seeming color films in 35mm––neither of the boxing movies, for example, or A Hell of a Guy, which seems to have a strong blue/yellow bias––but I did see Our Blood Will Not Forgive, which is more muted and blue than the other films of this era, and the more blue-and-grey color palette of that film was still quite saturated. There were some differences between the films with Shigeyoshi Mine as cinematographer––which tended to foreground these big panels of saturated color––and the ones where Kazue Nagatsuka shot them––he tended to highlight smaller, more subtle color expressions––and then there was some difference with films shot by other cinematographers, like Tattooed Life and Story of Sorrow and Sadness). To my eyes, the feature has much more depth-of-field here––maybe partly due to the broader range of contrast present in the feature transfer.

Trailer

Feature